What happens to wild horses that don't get dental care?

As many of you are aware, one of Dr. Butters’ special interests is equine dentistry. Knowing this, one of our fantastic clients generously provided us with a wonderful and very interesting skull specimen that we wanted to share.

This skull is from a stallion that lived in a wild/feral state west of Cochrane. Our client knew the stallion, and relayed that he died during the very cold, deep snow winter we experienced several years ago.

Dr. Butters believes she knows what may have contributed to this early death.

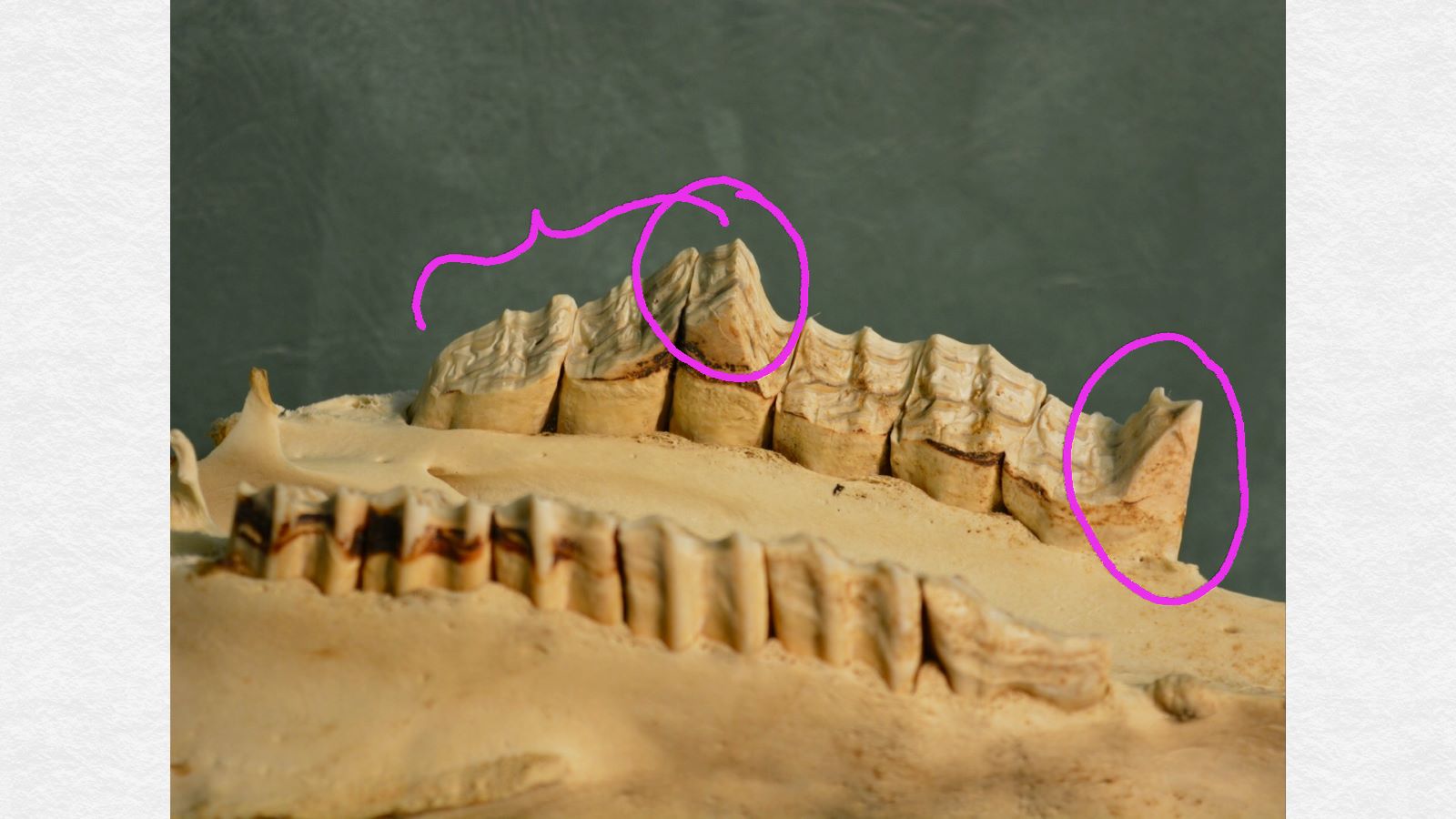

Note the stallion's "normal" side on the left, and the dentally affected side on the right (Note: there are some less significant abnormalities present on the left side as well)

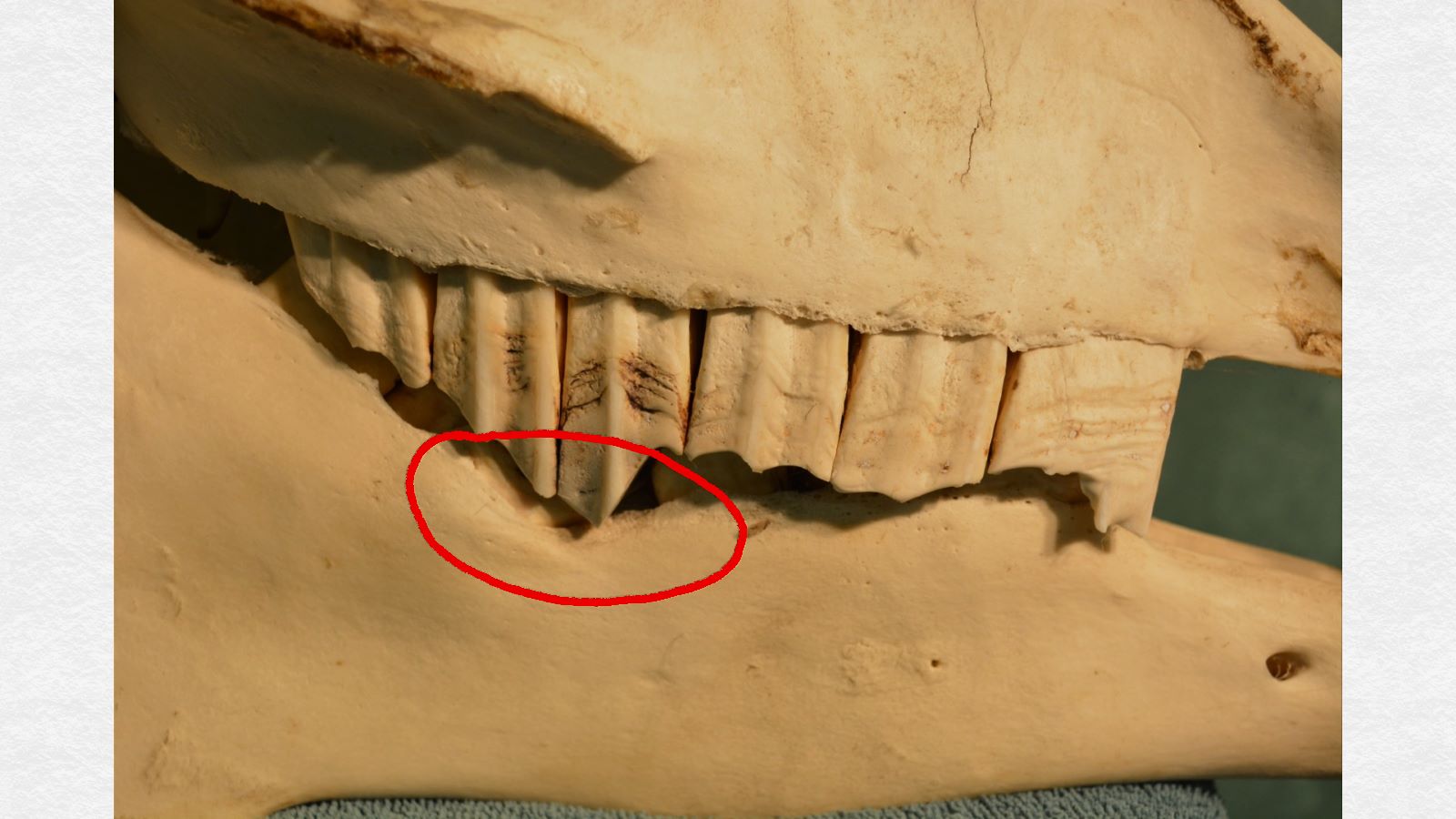

Severe overgrowth of the fourth right upper cheek tooth

This stallion had several dental abnormalities, but most noticeable is the extreme overgrowth of an upper molar in his right jaw. However, this is actually a downstream effect of the initial problem. It in fact began with a malformation of one of his LOWER molars.

The fourth right lower cheek tooth is small and tipped, with a space between it and the tooth in front of it

This malformation of the lower molar likely happened during the development of that tooth. On x-rays, we can tell that almost the entire root of this tooth is absent, with just a few small masses (possibly remnants of dental tissue) where a large root should be, and the clinical crown (portion of the tooth we would have been able to see above the gumline) is small and tipped.

On left: Xrays of the normal left lower cheek tooth. On right: X-rays of the abnormal right lower cheek tooth. Note the two long, slender roots present on the tooth on the left that are absent on the right. The xray on the right shows only a small amount of crown and a few strangely shaped remnants of potential dental tissue

Because the malformed lower tooth is not as robust or as firmly anchored as it should be, it was not able to adequately grind against the opposing upper molar. This upper molar then continued to erupt as it normally would, but was not worn down by the abnormal lower tooth during chewing. It became overly long and wedge-like and further forced the abnormal tooth (and the ones behind it) into an unusual position in the jaw. This wedge-shaped overgrowth “locked” his jaw in an abnormal position, and led to further overgrowths elsewhere in his mouth because his teeth weren't grinding against each other as they should.

The affected side. The back three teeth (left of the image, long blue bracket) are sloping toward the wedge-shaped overgrowth. The second cheek tooth (short blue bracket) is a little too long, and there is a prominent "hook" at the front of the first cheek tooth (blue arrow). The wedge-like overgrowth of the fourth cheek tooth "locked" the upper jaw a little forward of its normal position, so there was nothing to grind against the front of the first cheek tooth, hence the development of the "hook."

This is the upper jaw turned upside down. Note the overgrowths of the front tooth (far right) as well as the sloping nature of the back three teeth (on the left side of the photo). Also notice that on the "normal side" of the teeth (in the foreground of the photo), there is actually a little extra wear on the first tooth (far right).

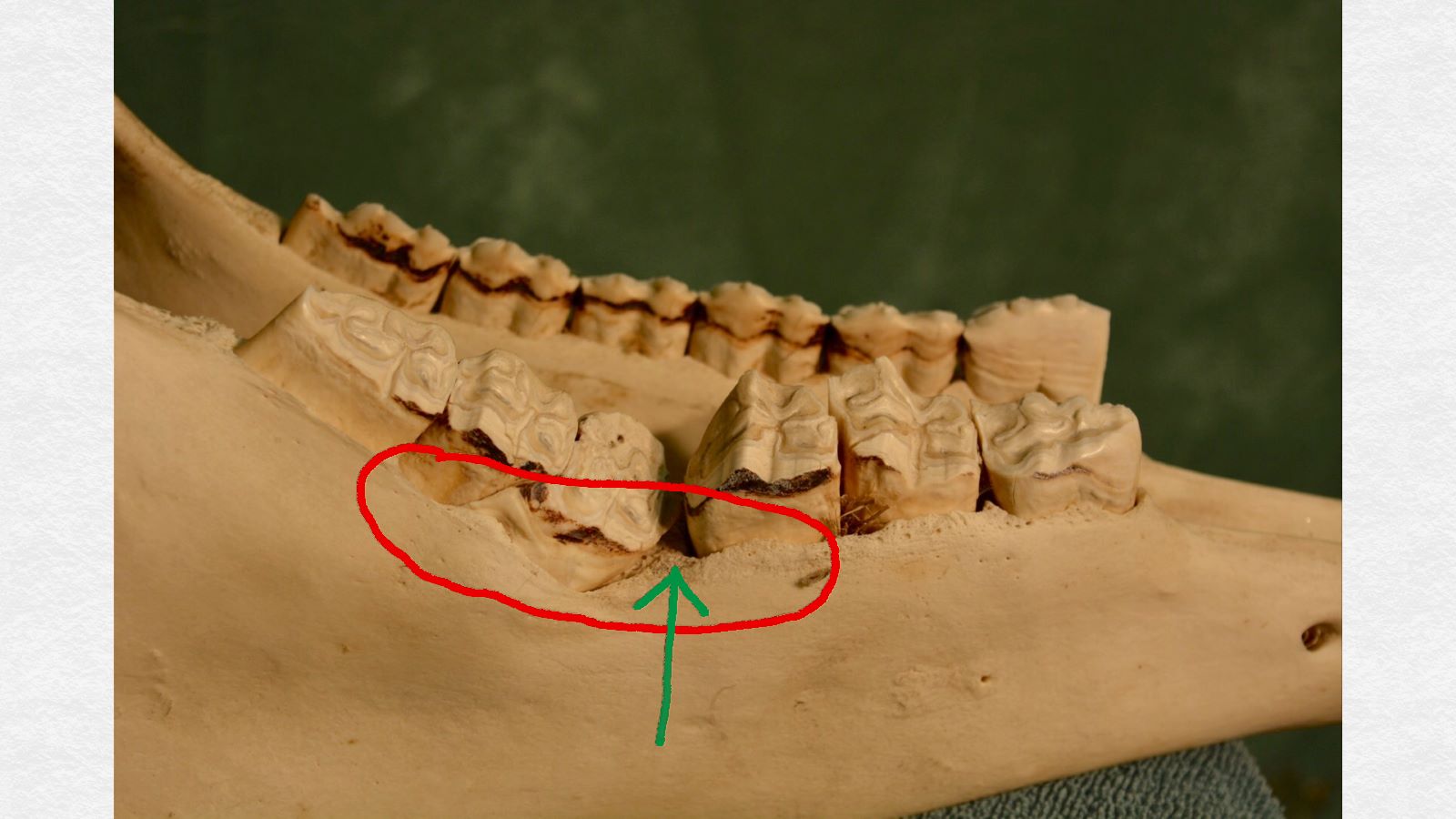

This had several effects. It limited the normal grinding motion of the jaw, probably causing the stallion to be less efficient in his processing of his food. Further, the wedge-like overgrowth of the upper tooth had become so long that it was actually wearing against the bone of the lower jaw, to such an extent that the bone had begun to change shape. Also, the space created between the third and fourth lower cheek teeth by the wedge overgrowth would have allowed feed to pack in the space. Like humans that don't floss regularly, this trapped feed fermented, bacteria flourished in the space, and severe periodontal disease would have developed. This periodontal disease erodes the bone in the area even more. This was likely incredibly painful for the stallion, causing him to eat more slowly and further compromising his ability to take in enough food during that long, cold winter.

Affected lower jaw

Notice the dip in the contour of the bone and generalized bone loss (red circle) in the region where the overlong upper cheek tooth was wedged between the lower teeth (green arrow). Feed would have also trapped in this area, causing periodontal disease

Compare the findings above with the smooth, level contour of the bone of the unaffected side (foreground).

This would be an extremely unusual abnormality in our wild/feral horse population. However, had this stallion been a domesticated horse, the abnormal overgrowths could be reduced by a qualified veterinarian to improve the function in his mouth, and minimize or prevent the painful changes to the teeth and bone.